Adam Milner on Public Sculptures in NYC

![Image caption: [L]: Adam Milner, "Pink Cookie Museum Display", 2021. Exhibited at a dog named Oh Papa, Manhattan, NY. [R]: Adam Milner, "My New Earring!", 2021. Exhibited at Conor’s Car (2003 Silver Honda CRV), Brooklyn NY.](https://images.prismic.io/black-cube/69af75bd-a06b-4886-9185-94c35caa027a_Adam+Milner_+%22Pink+Cookie+Museum+Display%22%2C+2021.+.jpg?auto=compress,format&rect=1,0,3047,998&w=980&h=321)

An interview with 2019 Artist Fellow, Adam Milner, on the opening of Public Sculptures, a dispersed exhibition featuring thirteen sculptures sited throughout NYC.

Adam Milner on Public Sculptures in NYC

Cortney Lane Stell: Each time I’ve had a studio visit with you, there’s an opportunity to nuance ideas, expand relations, and challenge reductive thinking. There is a plurality and openness in your practice that can be challenging to summarize. Can you share the core concepts or ideas that are central to your work?

Adam Milner: For me, the reason to be an artist is to stay open, stay uncertain, to nurture imagination, intuition, and criticality. I work across many media and processes, and allow myself to be influenced by a wide array of things. I have always felt a kinship with artists who seem open and whose bodies of work feel complicated and diverse. For me, staying open or porous, letting myself absorb and be absorbed, is an important part of being an artist. Even so, there’s still some rigor or focus there. I’ve been photographing my bed every morning since 2009, for instance. Lately my elevator pitch is that I make sculptures, drawings, books, videos, etc., which come out of personal experiences but point to greater systems of value, care, power, intimacy, etc. Really though, art is a way for me to inhabit the world: a way to be myself and to propose new ways of being, seeing, or thinking, if even for myself. Right now that involves slowing down to engage and consider these physical things I come into contact with throughout my day. These unassuming objects out in the world become the basis for these sculptural works: complicated gifts from loved ones or strangers, a bit of trash on the street, a luxury design object I fawn over, or a material and the opportunity to learn about it.

CLS: Throughout your practice, I see a reverence for materials that often breaks hierarchies. You've worked with found objects, bodily fluids, digital archives, precious metals, custom fabricated elements, display furniture, and much more. The mixing of all these materials seems to have a subtle yet poignant political nature to it. Do you feel that you have a deep respect for the material world that restructures or flattens common social orders?

AM: Definitely. I see everything as connected and always influencing everything else. Viewing the world through this lens helps me de-center myself, something that is sometimes very hard to do, even de-center the human experience, and get in touch with the world in other ways. I’m drawn to so many objects and materials all the time. Obviously it’s not anything goes, nothing feels random to me, but I do want everything to feel complicated when it’s together. I like how the theorist Jane Bennett uses the term “thing power” to describe how something can call you over to it, as if the thing or material actually has some agency in choosing me too. I try to stay open and responsive to the world around me, I try to stay sensitive, and I try to notice things. This leads me in different directions at once, and these disparate influences collide. This funny bunny bag thing from the thrift store, just a couple inches tall, appeared in my life and started to influence my thinking. Eventually, I just made a large replica of it. When blood or marble or bronze entered my work, it felt a bit out of my control. Those materials entered the practice, in part, through accident, through chance encounters with other artists and practitioners, which led to roads of curiosity that I followed.

It’s also about resisting easy identification or rigid categories. Working with a range of materials and processes is exciting to me, and it’s enjoyable. But it also reflects my desire to dismantle hierarchies, question norms, embrace the other, etc… queer things.

CLS: Public Sculptures is an exhibition that takes place at various locations throughout NYC. Can you tell us a little bit about why you are interested in the concept of a dispersed exhibition? What are your key inspirations, motivations, or ideas with regard to this type of arrangement?

AM: I usually work from home, and that kind of space has a big influence on how these sculptures are made and what conversations they participate in. Often, materials and objects — things I’m making, finding, buying, working with other people to make — move around the apartment and stack up and get arranged and rearranged. Then these artworks usually leave home and go into white cube spaces like galleries or museums; I don’t think of the gallery as their endpoint, but more as just a temporary context, for a month or two, or a year, then they come back home or go somewhere else. Sometimes I like the sculptures more when they’re with me, on the couch or bed or on the floor, or near something else that shifts its context. Dispersing the works throughout the city lets them each have a context that connects to their making or meaning in certain ways. These sculptures are made up of many different influences and vernaculars and showing them in collaboration with these sites allows them to be seen in a way that feels important to me. It was also about trying to put the exhibition out into the world in a way that people can encounter while going about their routines. Basically I was making sculptures and it made sense to me to show them here and there.

CLS: Many of the works in Public Sculptures are small-scale and intimate—they could be seen as challenging the ways we often perceive the role of art in public space (i.e. the canonical large-scale sculptures in public squares or massive murals on buildings’ exteriors or subways). Can you speak to the title of the exhibition, Public Sculptures? How did you come to this title and what intrigues you about it?

AM: Often the language around my work is somewhat soft and romantic. It felt kind of bold to say “Public Sculptures”. To call these delicate arrangements “sculptures” in the first place probably challenges some conventional thoughts around what sculpture typically is. I’ve liked calling myself a sculptor recently, especially on dating apps for instance, talking with strangers in general, because I find most people think of sculpture as a masculine practice which is funny to me. Some people I talk with imagine carved marble or cast bronze or something, and I actually am using those materials and processes, but in ways that escape the normal idea of a large, imposing, and permanent monument. The term “public” is also slippery and open. I am more drawn to thinking of an audience within local or intimate groups of people I know, not an abstract idea of “the public.”

CLS: Several of the sculptures presented in this exhibition are recently made, primarily during the pandemic from your home, and some of the exhibition sites are also close to your daily life. How are the lines between "public" and "private" space blurred in this exhibition?

AM: I think you’re right to touch on this, and they are inherently private things that I’m sending out into the public. A blurring of public and private is so central to my work, I think, that I often forget to talk about it, in part because any artmaking is already participating in a blurring of public and private — the privacy of a thought or idea made public by manifesting it and sharing it. For me, this always seems especially relevant because the things I’m interested in are often thought of as private or personal things: love, negotiation, trust, desire, generosity, contamination, domination… But these things are also political or have larger contexts, and manifest publicly in systems and structures. Because my work is made so intuitively and from my personal relationships or experiences, I’m always sharing fragments of personal things; even if the work is about something else, it still ends up having me in it. So sharing the work feels vulnerable sometimes. In this exhibition, the sculptures have been made pretty intimately at home, and with the help of friends, so their going out into the “world” is exciting to me, but in fact these sites which I’ve deemed public are still personal or private locations, to me or to others.

CLS: Many of the works in Public Sculptures have not been exhibited before, whereas others have been shown in exhibitions. Can you share any insights into the works that you chose to represent in this exhibition context? Why did you select these specific works and how do you think they exist within these new contexts vs. the white cube?

AM: I don’t think of them this way, personally. The idea of new and old sculpture gets kind of muddled for me. Some of these works incorporate or repurpose components from older works, and some have been previously shown as parts of other things. For instance, the ceramic bunny bag was first exhibited at the Mattress Factory as part of a bed sculpture called My Mountain, but in this exhibition it is paired with printed cellophane and becomes a new version of itself. The glass sword previously shared a small plinth with frescos of roses, but now feels like a new work in this context. Conversely, some of the sculptures that feel new to me actually have small components spanning many years. Potential Calendar has cast bronze lips (a cast of lip-shaped soap, really) and a bronze cartoony hand, which I made in 2016 in Mexico City as tests for my exhibition at Casa Maauad. Since then, that hand and mouth have been exhibited as a component of a few other works, including my temporary sculpture Remains at the Warhol. Now I’ve painted them with red enamel and they're part of this new work. This combination and recombination is important to me; often something I make or find makes its way into several iterations or versions of itself. I work pretty elliptically, constantly returning to things. Sometimes, things settle in... this is probably the final sculpture for these little pieces.

I love galleries and museums. And throughout the process of finding temporary homes for these artworks, I’ve come to realize that the white cube feels like such a safe space to share ideas. I don’t believe it’s a vacuum or void, but instead an interesting context to work within. These sites that the works get to temporarily inhabit are just as relevant to their making as more traditional art spaces. The reason I say that I’m suddenly seeing the gallery or museum as a safer space to share my work is that I can do anything in that context and it’s looked at as art and it’s considered a certain way. But putting the works out into places like a bodega, a tailor’s window, or a flower shop feels more vulnerable. To ask someone to let my artwork take up a little space and a little attention in their world feels like I’m sharing part of myself.

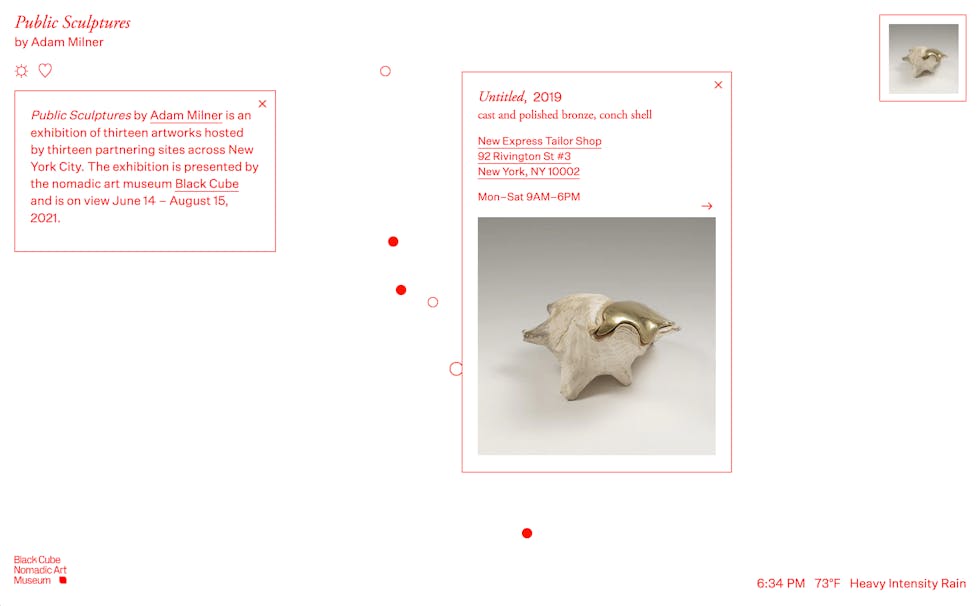

CLS: Many of the works have nested aspects, such as the conch shell and bronze insert (Untitled, 2019) or the nesting bell jars (also Untitled, 2019), while other works have related containers like the bunny bag or the green velvet display. Can you expound on this interest in forms of holding, nesting, or storing, that bring to the fore an interrelation amongst objects?

AM: A few years back I was trying to show the dedication and attachment I had to these little objects I was making and collecting, because they were easy to dismiss. I wanted to show off the items (an eyelash, a flower, a boyfriend’s tooth, a small Barbie shoe), but I also wanted to make legible the act of showing them off: the containers, surfaces, or supports that make it possible to highlight or make public something so subtle. I began making containers or things that held other things, very customized to specific objects, to show that this little thing belongs exactly right there. I realized I was slowly creating a sculptural vernacular around what care (slash comfort, protection, love, etc.) looks like…. But to contain something is also to try to hold it down, to lock it in place, so it’s a bit domineering, controlling. These tensions are exciting to me. The sculptures are really just the result of me processing and dealing with the things around me, which I have a fraught relationship with: I am attached to things, they are attached to me; they can be useful, or beautiful, or not; they accumulate, pile up, sometimes they take over, create conflict... collect meaning, accrue (or lose) value, become more important, or break. So in the sculptures I think there’s a push and pull of wanting to hold on or let go of these things, wanting to cradle them and slow them down, thinking they really matter and sometimes not being so sure, wanting to let them shine without my projections or bias, wanting them to stay active but also wanting them to be mine.

CLS: Tell us about the thirteen exhibition sites. How did you choose them? What kind of personal exchanges did they require? Were you interested in the neighborhoods or communities surrounding the locations?

AM: Similarly to how I choose materials or things within my work, they were chosen really personally and intuitively. Each site does something special that interests me, and each site complicates the group; there is no easy theme that they all fit into. . I was interested in many things: empty space, people and places I wanted to try to connect with, the design and aesthetic languages of the other made things nearby, and physically where they were. In the end, each collaborator is someone who said yes to me, who allowed these odd objects to take up some time and space in their lives.

CLS: Geographically the works are spread out into several boroughs. Can you explain your intentions how the exhibition may be viewed?

AM: It’s not meant to be a hunt. The website map serves to connect the sculptures and make legible the network that results from these different people and places choosing to host a work. It also provides a way for my friends and other people who care about my work, or someone who incidentally comes upon one of the works and becomes interested, to see the other works online and perhaps visit them. But I think the primary audience are the people who already regularly or occasionally visit these sites, and especially the people actually hosting the works. I hope that seeing the sculptures in familiar places or repeatedly as one goes about their routines lets people get to know them in a way that would be harder in the gallery or museum — more like hearing a song on the radio: how it changes over time, how your familiarity with it and your life experiences impact your experience of it, how it shifts from being noticed, to being in the periphery, to maybe being noticed again.

CLS: Following up on the idea of personal exchange, some of the locations require people to reach out directly to the artwork’s host (i.e. viewers have to text your friend Conor to get the location of his car or Starlee to coordinate a meetup with her dog, Oh Papa. Can you explain your interest in infusing these types of personal interactions into the exhibition?

AM: This is something that has always happened in my work, sort of by nature. I’m always putting my phone number into the world, or using mail or the internet to connect with strangers. The way that an art project, in its sort of inherent outsiderness, can allow for new modes of interacting or engagement has always been exciting to me. Projects or exhibitions often end up having some kind of network or connection that comes out of them, whether in their making or showing. All of the sites have agency over how the work is shown and discussed, and that was exciting to me… it’s very collaborative. In the case of the sculptures that are hosted really intimately by someone (Conor, Starlee, or Keiko), as opposed to within an institutional or business context, they can engage people who text them in whichever way they choose. I like that there’s that flexibility there.