Inside the Cadet Chapel w/ Jaimie Henthorn

Black Cube interviewed 2018 Artist Fellow Jaimie Henthorn about her experience producing a film inside Colorado’s iconic United States Air Force Academy Cadet Chapel.

Inside the Cadet Chapel w/ Jaimie Henthorn

Black Cube: You are a trained choreographer and dancer, when did your work start to bridge into the field of contemporary art?

Jaimie Henthorn: What I considered a fine art practice and dance ran in parallel lines for years as strangers, as far as I was concerned. During my BA at Northwestern, and Chicago generally, we learned about the meshing and melding of disciplines by the Bauhaus or Judson Dance Theater. I danced, including learning from Robert Battle and Juliard instructors at Perry Mansfield and dancing with Khecari Dance Theatre and Wise Fool NM in Taos. My studio practice then began to explore built space with large scale installations and direct mark making. I did away with the canvas and the frame and then, during my MFA studies in Scotland, I realized I didn’t need to make marks any more and could feature the body itself. This was the big “ah-ha” moment and I never turned back. The focus of my research developed into working with the body as my instrument and built space as my context.

BC: Much of your work deals with the combination of the choregraphed human body and modernist architecture. Can you orient us around this interest of yours, and why it has been an ongoing area of research?

JH: Modernism is a convenient subject given the vigor of the theory and prevalence of buildings in the built landscape today. It is old enough that we can reflect on it and new enough that we still care about it. Plus, I really like its aesthetic, bizarreness, and controversy.

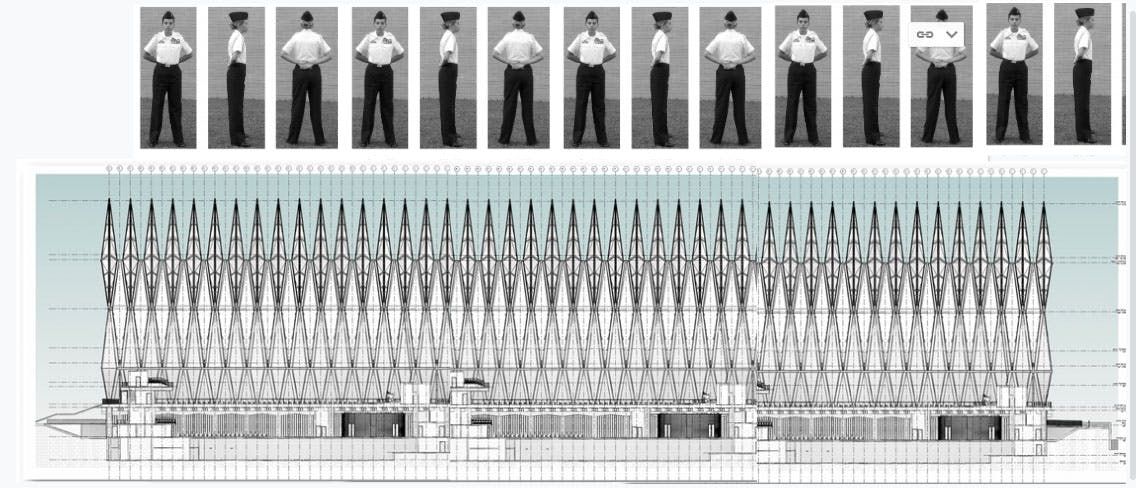

Each of my performance investigations engages a modernist building in deep conversation with the human body. I am interested in the way we move, learn to move, and are instructed to move in relation to these architectural structures, specifically in terms of power and identity. Coming from a dance background, I utilize the ‘moving body’ as my research tool to expose the relational dynamics between built environment and human subject.

BC: Designed by American architect Walter Netsch, the Cadet Chapel is the most visited man-made tourist attraction in Colorado and the most recognizable building at the Air Force Academy. Why did you choose to engage this iconic space for your fellowship project?

JH: Part of the answer is in the question. This is an icon of the state and proved to be the most recognized building of Netsch’s career. Being on the Air Force Academy campus added an interesting layer to the social context – the adoption of the Chapel into military culture and values was apparent. I find the more there is to unpack with a particular structure, the richer the research process and the stronger the outcome of the project.

BC: This project required multiple layers of permission for both filming on site at the Air Force Academy and collaborating with the Cadet Honor Guard. Can you speak about the process for obtaining permission?

JH: Seeking permissions comes with the territory of working with known modernist buildings. Many are historically registered in one way or another. I sussed out the permissions route and waited to receive the artist fellowship and alignment with Black Cube to communicate with them. The proposal had to be approved by the resident architect and the legal team. In order to work with the cadets who practice drill, I was required to use the Cadet Honor Guard. Then, once we had footage, it all had to be screened by their legal team. These processes were tedious and drawn-out, but it is actually quite informative to get inside the communication loops of the organization to learn more about it and get to know people.

The cadet honor guard was chosen for me as the performers by Air Force Academy, and I had a chaperone at all times. This degree of control over my actions was hugely influential over the final outcome of this video work. Through the duration of producing my work at the U.S. Air Force Academy, I experienced a meaningful collaboration with the cadets—one that revealed their rapidly evolving sense of self and a more direct correlation with the Chapel to that sense of self than I could have imagined previously. Experiencing the space where young cadets form their sense of self and identity, under the pressure of power structures that demand an orderly veneer.

BC: The video is scored by American electronic music producer Kate Simko, in collaboration with the London Electronic Orchestra. Why did you want to work with an electronic dance music composer on this work?

JH: Once I knew this would be a video with AFA cadets as the subject, both due to permissions, I wanted it to do that sort of magic thing that I had seen with military-style movement as dance. I was obsessing over Janet Jackson’s Rhythm Nation video and also step dance use of drill movement. Knowing I would be sticking with the cadets choreography for the most part, I played around with overlaying music on drill competion videos sourced online. I know Kate through friends and knew about her fascinating innovations with creating the London Electronic Orchestra and scoring and performing orchestral arrangements. Its freshness and beauty evoke something I can’t describe and that means many things at once.

BC: You approached two highly charged subject matters in this artwork: the military and the church. Yet, the video itself manages to present neutrality, focusing more on the cadet’s body movements in relation to their built environment. Do you agree? Was this intentional?

JH: I mostly agree, yes. I think the video presents neutrality as far as aligning with one camp or another about the relative value of these huge institutions. This video is about humans and the structures we build and live in and with. I also want viewers to really see the content for what it is and not shut their mind to it or even be concerned with it supporting their own agenda. I do think there is a charge to the work in the way it brings up power structures - architecture’s implicit involvement and the cadets’ vulnerability.

BC: Repetition and mirroring are key techniques that occur throughout the video, both conceptually and visually. Can you explain some of the moments when repetition and mirroring occur? Why did you utilize these methods?

JH: The mirror became the driving concept of the work once I understood to what extent the Chapel as emblem of the AFA is instilled in the cadets. I really don’t think it bears much religious meaning for them – instead they see their inspiration, goals, their cadet selves reflected back at them. This is employed as a motif in the video with left-to-right and top-to-bottom mirroring effects. And the video as a whole functions as a mirror as well, journeying forward and then back again. This gives the viewer time to reflect on the experience while still in it. Because of the symmetrical and regular nature of the forms and movement, these motifs and even the video running backwards integrates fairly seamlessly.

BC: Black Cube’s fellowship is intended to help artists grow in their art practice and often experiment in uncharted territory. How did this project help you grow? Were there moments when you were challenged or inspired?

JH: I learned to turn out a more finished product. I feel confident in my abilities to fine tune a concept and create a compelling concept. Then moving from project to a finished artwork has felt elusive, something I would land of if lucky but not have much control over. I could now define and describe that process from working as a Black Cube fellow, and hopefully repeat it!

The challenge and inspiration were both wrapped around that process. I felt confused and disoriented at times in pursuit of a final video product. I was also wildly pleased when the collaborative elements we had worked so hard for came together in a way that aligned with the original vision. That was magic.