Institute for New Feeling on Avalanche

Black Cube’s Executive Director + Chief Curator, Cortney Lane Stell, sat down with artist collective Institute for New Feeling to discuss their wider practice and fellowship project Avalanche.

Institute for New Feeling on Avalanche

Cortney Lane Stell: How did you meet? What made you decide to become an artist collective?

Institute for New Feeling: We met in grad school at Carnegie Mellon University. We had collaborated in pairs on a couple of earlier projects, and after finishing the MFA, we created the Institute as a kind of umbrella that could contain a lot of things we were doing and thinking about. We'd been making time-based experiences that were often very intimate, physical, or even metaphysical in nature. As a group, we started framing these as treatments and therapies, taking on--and thereby problematizing--the authority of health, beauty, and wellness marketing. Over time, the collective has grown and shifted to encompass many different ways of working; from video to virtual reality, sculpture, performance, text… Interests also change over time, with different projects turning to focus on subjects like online privacy, SEO marketing, invasive species, catastrophic weather events, political longing. Our work typically follows thematic trajectories, rather than committing itself to a set process or structure. For this reason, the Institute’s identity is kept intentionally elusive. At times, we’ve called ourselves an art collective, a corporation, a spa, a research institution, a marketing firm, a lobbying group—the only true consistency is flexibility and change.

CLS: Tell us a bit more about the Institute for New feeling (IfNf)? How did you decide on the name?

IfNf: The name was also designed to contain a degree of ambiguity. In everyday conversation, “feeling” can refer to a physical sensation, an emotional state, a spiritual inclination, even an opinion or belief. Once, in conversation, a friend described a YouTube video he had just seen as disturbing, funny, and sad at the same time, saying he felt a “new emotion.” This phrase stuck around. It seemed an important demarcation of our time, and a term that could be used to describe the kind of artwork that defies simple interpretation--meaningful, memorable, yet hard to pin down. In this sense, our use of the term “new feeling” was somewhat aspirational. Just as it embraces contradiction and liminality, the term also lends itself to explorations of “feeling” that is altered, filtered through, or enhanced by technology. Although we may market it with a tone of commercial confidence, in reality, we’re interested in “new feeling” as an ongoing field of research.

CLS: Can you describe your group dynamics? How do you all stay connected even though you live in different areas?

IfNf: We don’t have a hierarchy or consistent division of labor--rather, we try to involve all three members in every major decision. At the same time, we’ve rarely all lived in the same city. So, our conversations have become heavily mediated and dependent on technology. It’s not uncommon for us to work all day on Google Hangouts. Our message threads complex, multi-tiered conversations across every platform available--sending images and reference links by text message, What’sApp, Slack; showing each other materials and sketches over Skype or FaceTime, or building a vast archive of Google spreadsheets. There are times when we’re on the phone but not even talking--just working “beside” each other, making lunch or walking the dog. And this virtualization has seeped into our work in significant ways. At times, unintentionally, our projects nearly always take on some aspect of contemporary digital life, often playfully reflecting ways that technology has shaped our physical, intimate, and interpersonal realities.

CLS: Tell us a bit more about past products that IfNf has produced?

IfNf: In 2012, we launched a product line; a body of sculptural work that functions imperfectly as speculative design. To date, our products include: a branded reflexology insole for the foot, a concrete neck pillow, edible earplugs, blinding contact lenses, and an odorless air freshener filled with a neurochemical called Oxytocin, fragrances based on the air quality and psychological state of a community, and a cream that accelerates aging. Each of these products provides an unfamiliar or altered function; instead of meeting an immediate need, they seem to always pose more questions as to who they are meant for and how they should be used.

CLS: How does this upcoming project, Avalanche, connect with some of your past works?

IfNf: Throughout our product line as well as our VR shopping interface Ditherer, we’ve been persistently interested in exploring the myth of the “source” in product advertising. From shampoo to cereal, we are all familiar with the narratives stitched together by copywriters and video producers regarding the quality ingredients, family-owners, sustainable farmers, and authentic recipes that make a product attractive for purchase.

And especially alongside the expansion of organic/local farming, the rise of Whole Foods and trends in responsible consumption, these questions of “where our products come from” seem more relevant than ever. But, who is equipped to answer them? Who should we believe? How far down the rabbit-hole of research must one go in order to call a purchase “responsible”?

The primary question we get asked—with Avalanche, as with many of our other projects—is: Is it real? Is the filtration process depicted and the avalanche that results actually happening? We believe this type of scrutiny could be applied to any bottled water product if consumers dug deeply enough. There is some awareness out there today that most “mountain spring water” is actually filtered tap water; indeed, regulations around bottled water are often less strict and require less frequent testing than municipal water in this country. In this sense, purity is an aesthetic, not a tangible reality.

For Avalanche, we’ve created our own strange mythology—mashing up the pristine mountain spring with the trickle of water across a dirty windshield, the gargle and spit from a teenager’s mouth. And the moment of transformation (i.e., sterilization), of course, occurs via a technological sleight of hand. As the last step of the filtration process involves converting wastewater into sound waves that cause a recurring ecological disaster, Avalanche water initiates an environmental feedback loop that can’t be undone.

CLS: How did IfNf develop the enhanced water brand Avalanche?

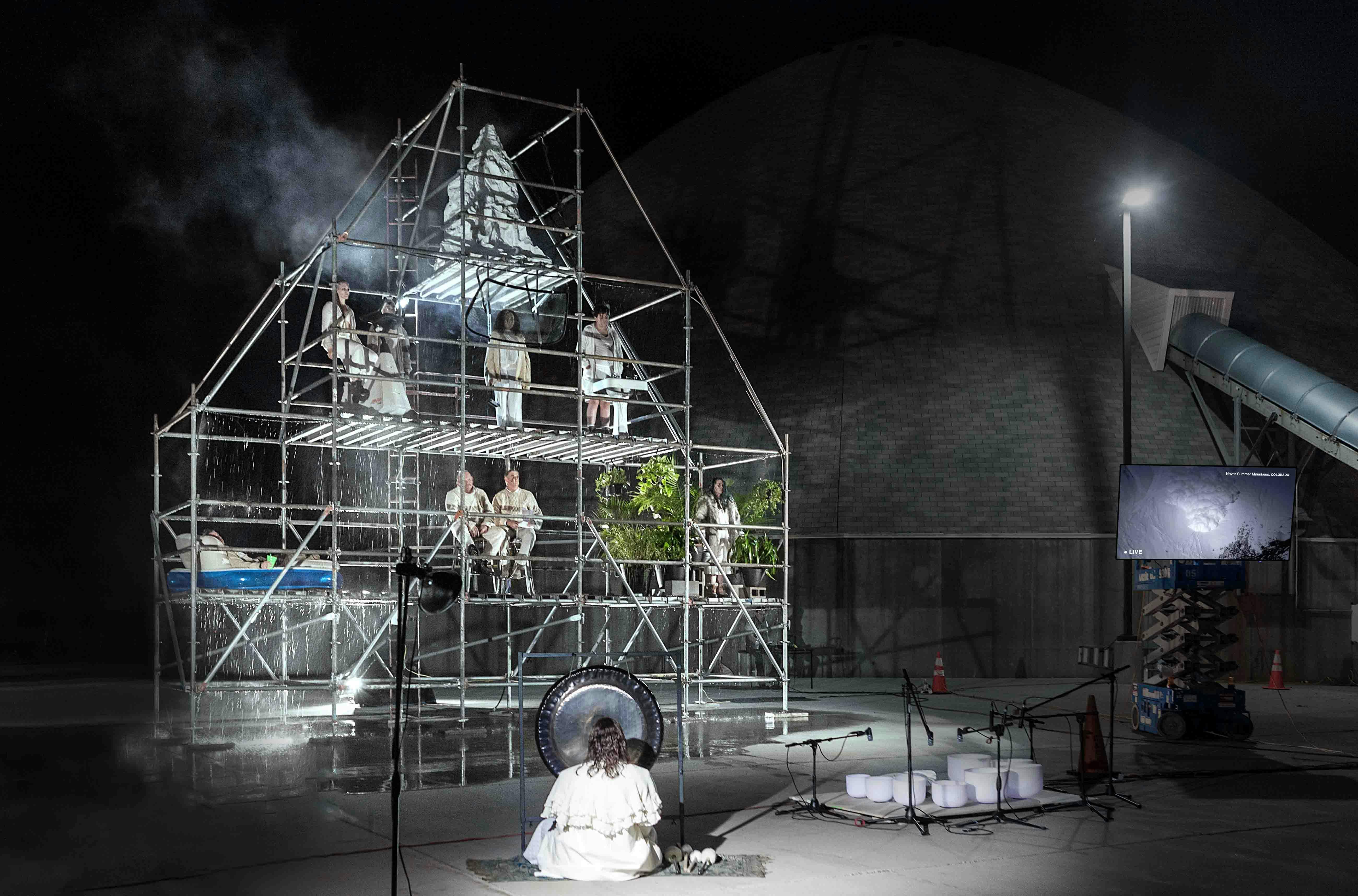

IfNf: The initial idea for Avalanche came about during the height of the historic drought last year in Southern California. We began with an image of this vertical scaffolding system that uses gravity and live performers to pass a precious stream of water from the top to the bottom. As with many Institute projects, we were thinking about all the “wrong” solutions that an organization like IfNf might propose in the face of such an apocalyptic water crisis caused by the irreversible effects of climate change. So on a very basic level, the project proposes an absurd solution to a very real problem. Running out of tap water? Buy bottled water. Indeed this kind of thinking seems to uncomfortably embrace the Anthropocene, implying that water could be somehow enhanced by humans, rather than simply contaminated; dirty water causes a natural disaster, which in turn provides an absolute source of purity.

On the other hand, any simple critique of the bottled water industry might also be problematized by the fact that bottled water is not only a wasteful product of the upper classes—it actually provides a critical source of clean drinking water to populations at highest risk for contamination. Within this framework, the Avalanche brand appears particularly dark; issuing a kind of heartless corporate let them eat cake.

CLS: How does the performance relate to the bottled water brand, Avalanche?

IfNf: The performance is essentially an elaborate staging of the filtration and bottling process behind each bottle of Avalanche water. We think of it as a kind of sound installation, a literal concert of bodies manipulating the flow of water through these simple tableaus of everyday usage (hydrating a workout, cleaning a car, watering plants, brushing teeth, etc.). Audience members can sit and listen to the sound of the water melting, dripping, sloshing, and resonating through the performance, interpreting the actions on the scaffolding with a printed diagram, and also purchase a finished bottle from a branded vending machine.